Some thoughts from one of Saint-Denis’s students, by Jeremy Geidt

Actor in Group One at the Old Vic School and after a tour with the Young Vic Players taught for three years at the School. He acted at the Old Vic, The Royal Court, in the West End, in films and on TV and had his own variety T.V. show « Caravan »on the BBC for five years. He had also done political cabaret with « The Establishment » in London. Chicago, Washington and New York. He has lived in USA since 1963 acted both on and off Broadway and in 1966 taught at the Yale Drama School and acted in the company. In 198O he moved to Harvard and the American Repertory Theatre and has been teaching and acting there ever since acting many wonderful parts.He acts very little now and mainly teaches.

I first met Michel St. Denis in a cold, dingy, unfriendly rehearsal room, somewhere off the Waterloo Road in London, late in 1946. The war had just ended, rationing was still in force and the country was drab, tired, pale and lifeless. However, a new light , a new sun was about to shine its bright sparkling genius on the theatrical scene; not that I, a spotty, awkward sixteen year old could have told you so then.

I had recently left my English public school or perhaps a more truthful way of putting it would be that my House Master « suggested » that I should leave the school. It didn’t take much acumen on his part to realize I was a rotten student academically but, for some reason, he thought I might possibly make an actor. I guess he saw precious little future for me in any other walk of life and had been an aspiring actor himself many years before and knew something about the business.

He had read that The Old Vic Theatre Centre was about to open with the Theatre School at its heart. He told my parents he felt I could handle « old fashioned theatre » (I’d got some laughs in school productions of plays by the likes of P.G. Wodehouse) but was not certain of a future for me in « the modern theatre. » But, if it were possible for me to gain entry to this new and exciting school that would be my trial by fire; and if I could handle « the modern theatre » there might be a chance for me in the profession. Luckily a friendly German bomb had kindly blown me down some steps during the war, injuring my knee making me ineligible to be ‘called up’ into the armed forces so if I could get into the school, all would become clear. Which brings us back to that dreary room in the Waterloo Road.

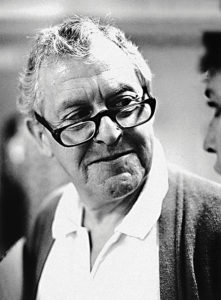

I was there to audition for The School. Behind a rickety trestle table looking fierce (to my eyes) were Glen Byam Shaw, George Devine and a short , pleasant looking, pipe smoking Frenchman. Even at that age I thought he had the face of « an aristocratic peasant. » Little did I know how much this amazing man was to influence the rest of my life.

My mother had asked advice from a theatrical acquaintance of hers, Celia Johnson, she of the world’s best tear jerker Brief Encounter, for audition ideas for me; she suggested Iago’s « Put money in they purse … » and Collins’ unsuccessful proposal to Elizabeth from Pride and Prejudice. Maybe not the best of ideas, but how was Miss Johnson to know and there we were. I struggled through them as best I could with nods, « Hmmms » and much pipe puffing and cigarette drawing from the gents behind the table. There was muttering from the three and I was asked to wait outside where a kindly, handsome Pierre Lefèvre tried to cheer me before he was called back only to return with an idea for an improvisation the Big Three wanted me to do. « Sitting on a park bench » was the subject, as I remember; not much to go on but I had to have a go, not even entirely certain what ‘improvisation’ was.

Back I went into the cold, dingy, unfriendly room where Pierre placed three chairs together to make a park bench upon which I sat as instructed. Of course an imaginary dog came along; as I’ve always liked dogs I felt a friend had come to my rescue. He smelt my leg, licked my hand, ate the remains of my imaginary sandwich and after lifting his imaginary leg on my shoe, left me. A tramp came along and we (one-sidedly) discussed what little I knew of the world. There were a few grunts and smiles from The Big Three, encouraging laughs from Pierre before the improvisation was mercifully called to a halt.

« Come and sit here, » I was told by George Devine indicating a chair in front of the rickety table. The usual questions were asked; Why did I want to be an actor? (I just wanted to … had to.) What acting had I done? (Not much.) Why did I choose the Old Vic Theatre School?(I’d heard it was good … what else could I say?) More of the same then Glen Byam Shaw asked me, ‘Who is your favorite actor? » Before I knew what I was saying or thinking I blurted out, « Sid Field, sir. » As the words left my lips I realized to my horror I should have said Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud or some other great Shakespearean. Saying that a Music Hall comedian with a strong Midland accent was my favorite actor was obviously not a ticket into the exclusive Old Vic. I was sunk. Or so I thought.

At the mention of Sid Field the short, pleasant, pipe smoking Frenchman sprang not only to life but up onto the rickety trestle table where he sat precariously, crossed- legged with a wonderful smile on his face. » You said, ‘Sid Field?’ I too think he is wonderful. » My heart leapt. My thoughtless, but sincerely meant instinctive reaction (my blurt) must have been God sent. It seemed that this wonderful Frenchman and I were on the same wavelength.

If you have no idea who Sid Field was, I’m not surprised. He died in 1950, aged 45. He had toured the provincial music halls for many years before coming to London in the revue Strike A New Note in 1943 and from then on was the toast of the transatlantic theatrical profession (not that I knew that at my audition), pioneering character comedy and not simply stand up. This, his remarkable talent and his ability to improvise so many various characters, was obviously what fascinated Michel St. Denis. I, the neophyte, couldn’t analyze all that; I just thought he was wonderful and to this day I’m sure it was Sid Field and not my audition that got me admitted to the Old Vic Theatre School.

As indeed I was. My serial number on the acceptance letter was A 1; as this obviously didn’t apply to my talent, I think it only meant I was the first student to be accepted into the School. And so in January 1947, the coldest winter in England since 1814, began the warmest winter of my heart’s content. It began on the stage of the roofless, bombed Old Vic Theatre where we sat shivering while Laurence Olivier warmed our hearts with that thrilling voice, inspiring fellow students, teachers and other « very important people » telling us we were about to change the face of the British Theatre.

Obviously we couldn’t train to change the face of the British Theatre in a bombed-out theatre, its auditorium full of old sets from ENSA war time shows for the troops and for some reason piles of coal upon which rats often played so we were transferred to an unheated building lent by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School in Barons Court on what is now the M 4 Extension. The weather and the building were freezing, the only heat being generated by the student’s breath after a hard physical class led by the great Litz Pisk. And, I guess, from the warmth in our hearts of actually being there and being trained by wonderful teachers led by this genius Frenchman.

Anybody visiting this web site knows about the training at the Old Vic Theatre School from Michel’s own books and those written with knowledge and deep professional insight by Jane Baldwin, so let me skip that and the horrors of the « the test » where the students were thrown in at the deep end of a classical play to show their weaknesses (in our case, Group One, it was Anthony and Cleopatra directed by Glen Byam Shaw, and it generated my first criticism from M.S.D.: « Jérome, you really cannot think you can play Caesar just by walking around with your hand on your hip. ») and let me remember Michel St. Denis not only as a teacher but as a man.

And there was a man. A man who instilled in me from the start that the secret of life was « zee truce » which is how I heard M.S.D.’s pronunciation of « the truth ». To continually search for, to continually explore and dig for the truth. Not only in a theatrical text and in one’s acting but in all of life. I have taught acting from the early 1950’s (when I returned to the Old Vic School to teach) and every time I enter a classroom I hear his voice in my inner ear telling me to look for and try to teach « the truth. »

He could be harsh, strict and somewhat hurting in his criticism as I soon found out. After one showing of some solo improvisations, Michel went down the line dishing out praise or helpful condemnation. He came to me; hardly looking at me he waved his hand in a contemptuous dismissive way, pursed his lips and let out a Bronx Cheer or farting sound and went on to the next student. Obviously I had been showing off and taken a thoughtless easy way to an untruthful result.

Some would say his critiques were cruel, if so they were cruel only to be kind and, if one was honest with oneself, one knew the severity was only to illuminate the lack of « zee truce » in one’s work. Anyway, in my case the rude Bronx Cheer must have worked as in a couple of years I was back at the School teaching and working as his assistant. I was flattered, delighted and terrified to be asked to teach, particularly as I was younger than many of the students. I remember asking Michel of what my first class should consist; he thought for a moment and then said, “Jérome, I think you should teach them how to whip up a dull Saturday matinee. You are good at that and the students are so serious and solemn about their work.”

It was not the answer I had expected from the greatest of teachers, but in a way it was the right one. He was a man who embraced the theatre with such passion it was frightening, yet he never took it “seriously” in a puritanical way. He loved it far too much not to be able to laugh at it and with it.

As a student I had been quite successful at comic mask work and gags so for my first class I made a list of comic tricks for the students to work on. I can still remember looking down at my paper, slightly damp and shaking with ‘teaching/stage fright’ at the list ; basic comic tricks like : belching, yawning, snoring, slipping on banana skins, getting hiccups, tripping and falling off chairs while swatting a fly; tried and true music hall stock in trade stuff. This seemed to go quite well and when reported back to Michel the news was met with nods and a congratulating smile.

I was lucky enough to be asked to stay and teach; not only ‘gags and tricks’ but also improvisation (at first with Michel and then alone) with the ‘straight’ four ages masks and the character comic masks (at first with George and then alone). I also worked (at first with Suria and then, again, alone) on group improvisations until I was teaching many classes from make up to scene studies. I stayed at the School until its tragic end. A tragedy not only for Michel but for the entire British theatre. All of which has been well and fully written about by Jane Baldwin.

I’m sure I learnt far more than I taught; lessons, ideals and a real belief in the beauty, magic, truth and imagination that makes the theatre the wonderful place it can be.

One of the many lessons I learnt from Michel seems so simple, unadorned and unsophisticated that in the telling it sounds too trite for words, but it taught me a lesson that I’ve kept close to my heart all these years. It was lunch time in the small, friendly little canteen in our Dulwich school building. I had just taught a good mask class but one student had giving me a most difficult time telling me she thought the work was “vulgar and unnecessary for an actress to learn.” Getting my lunch, I took my tray and sat alone at one of the small tables. Soon, Michel came in, got himself his lunch tray, looked around for an empty table, saw mine and asked if he could join me. (Ask?! I was flattered!)

He looked tired; I knew he was rehearsing Electra with Peggy Ashcroft and that rehearsals were going through a difficult time. But he still wanted to know how my classes were going. I told him of that morning’s difficult student. “Ah, Jérome “ he said,” when teaching you must remember however resistant a student maybe, you have to sow a few seeds, then later a little rain falls on those seeds after that the sun comes out and eventually those little seeds you have sown bloom into lovely flowers.”

Well. That hardly sounded like Stanislavsky or Michel at his fiercest during a scathing group criticism session. It was so Pollyanna, so simple and so childlike. But it comforted me and I tucked it away in my teacher’s knapsack and we talked of Electra.

A few years later I was at a party when the difficult student, now turned into a very good and successful actor had just come from rehearsal of a play in the West End. She came up to me looking slightly shamefaced. “Jeremy, remember that mask class where I was such a pain?” (I certainly did.) “ Well, you know what? It suddenly all made sense to me during this afternoon’s rehearsal and things sort of clicked into place and it helped. I just wanted to say sorry and thank you.”

So there it was. Michel’s “few seeds, a little rain” and the sun had come out. Michel had again taught me, a young teacher “zee truce” and one I’ve tried to remember all my teaching life. Also, that an actor should be ‘childlike’ in his approach. Childlike in the same way a child plays his games and an actor should play his plays. Childlike, not childish.

There was certainly a childlike side to Michel though he usually hid it behind his authority, but his sense of fun and humour often burst through. Many times he would start faculty meetings regarding the students’ progress by asking me “Now, Jérome, which of the girls do you find the most attractive” which always broke the ice.

I remember having several dinners with him and Suria at their tiny but most elegant flat in Earls Terrace just off Kensington High Street. They had been most generous to me allowing me to stay in their (very nice) basement-cum-storage spare room when I was out of work after the School closed. He would laugh and quarrel with Suria over dinner and delight in showing a cracked pane of glass in a corner cupboard where George (Devine) had thrown a pepper pot in a temper having cracked the frame of a chair with his weight. He loved George but loved to laugh at him as well.

He sometimes gave little parties with people who had worked at the School. Some went on quite late; too late for Suria who once, at about one in the morning curled up and dozed off on the white rug in front on the fireplace above which hung his wonderful and prized painting by Braque. He taught me how to drink wine and now I was holding an empty glass. Thinking I was so bloody smart and sophisticated I spat on my hand and rubbed it round and round the rim to make that humming noise. “Oh, no, no, Jérome! No! Pleeaase that’s not a good thing! You sound like a commercial traveler trying to impress.” A teacher to the end of the party.

I often think of him as my second father and I sometimes wonder if he didn’t sometimes think of me as a sort of second-rate surrogate younger son. His much loved eldest son was also called Jérome and had been killed in Alsace at the end of the war.

I believe it may have been the anniversary of Jérome’s death sometime in a January that Michel and I were traveling up from the School in Dulwich to Victoria Station and he asked me to go with him to a small, quiet pub nearby. We had a few drinks (he never let me pay) and he then began to speak half in French and half in English and for a little while (a very little while) became slightly teary talking of Jérome and what a waste and how ironic that his death should come so near the end of the war.

But I never saw Michel sentimental; he allowed sentiment perhaps but nothing sentimental and soon his natural resilience and tenacity swung into place and with a warm smile and slight hug he was off to Suria and me to my digs.

That resilience and tenacity was never seen to greater advantage than it was during the time of the disgraceful dissolution of the School and the end of his vision of the Old Vic Centre. The “Three Boys” had been fired but only one didn’t seem down in the dumps despite the shattering of his dream. The rest of the faculty resigned in sympathetic and angry protest; however, we managed to get that news to the press before Old Vic Governors did which pleased Michel a great deal. A small victory against the swine, but a victory which brought out that wonderful smile. Those qualities along with his phenomenal energy and imagination are qualities that maybe I remember the best.

As a director he could almost mesmerize an actor during rehearsal; his energy seemed to hypnotize one into finding more in a part (and in oneself) than one had thought possible; he questioned actions; he inspired with suggestions and demanded more and more from the actor. His rehearsals seemed to transport one into a different and magical world.

I can remember rehearsals of Chekhov’s one act farce The Festivities for The Young Vic Players (a bus and truck offshoot of The Young Vic) during which he had gone on and on at me to get something right, when suddenly he said “Oh, good. Well done. Time is up. We must finish now.” I thought that we’d been rehearsing for about half an hour, but not at all. It had been a four hour rehearsal but those four hours with Michel had only seemed like half an hour. The concentration and imagination was so intense that the time just flew.

And the years flew and Michel’s health and life flew far, far too fast. Much has been written about his last years, his successes and his declining health. So from me just the last memories of great man who helped to shape my life.

In 1966 Robert Brustein had been made Dean of the Yale School of Drama and being an admirer of Michel’s work and theories had asked me to teach there (and eventually act in his company.) On a trip back to England in 1967 I made contact with Michel and Suria who kindly asked my wife Jan and myself round to their little house in Bloomfield Terrace off the Pimlico Road in London. We were delighted of course and off we went, slightly nervous but I was so happy for my wife to meet the man who has meant so much to me. We were welcomed with gracious affection and a nice glass of wine; Suria looking as chic as ever; Michel slightly frailer and, of course older but in fine form.

Dinner was to be on them and we walked slowly up to a small restaurant on the Pimlico Road where the St.Denises were welcomed with fine Italian warmth and great respect; obviously much-liked regulars.

Michel, as usual, talked all through dinner; remembering, asking, teaching and joking. Dinner over we thanked, said goodbye and were about to set off home via Sloane Square Underground station when Michel insisted that we come home with them so we could talk some more. I hesitated; Michel insisted; Suria whispered “only for a very short time, he must rest.” We walked back down Bloomfield Terrace, Suria and Jan in front, Michel and myself slowly behind, Michel holding my arm and leaning on his stick. Halfway home he wanted to sit down so we did, on somebody’s door step, Michel still talking away.

Back in the house we were offered more drinks by Michel, with Suria still whispering “only a very short time.” But I don’t think anybody ever stopped Michel when he seemed to be enjoying himself and the several times we tried to leave he started up again, much to Suria’s concerned frustration. I knew we had to leave when he started calling me Peter. This I couldn’t make out until Suria pointed out to Michel that “Peter” was Peter Ustinov and that I was not Peter but Jeremy or Jérome. Ustinov had been a bit of a bad boy at the London Theatre Studio before World War II but I believe had always amused Michel. Then I remembered that once when my mother had met Michel he asked her, “Your boy is doing all right, but why is he always so funny?” It was late, Michel had suffered three strokes in his life and I now know myself how easy it can be to muddle ex-students names and dates; in a way I was most flattered that one of his (now famous) pre-war students and one of his (not famous) post-war students should be confused in the great man’s mind, a mind so concerned with actor training; a confusion easy to understand. A confusion made by that still bright, sparkling genius.

So that was it. A “few more minutes” went on till just before midnight when kisses, goodbyes, smiles and laughter were exchanged between all four of us. Well, all five as I was still “Peter-Jérome” and off we went; the last I saw of my brilliant and courageous teacher whom I loved so dearly.

Jeremy Geidt