The London Theatre Studio, by Sophie Jump

Michel Saint-Denis and the London Theatre Studio, by Sophie Jump

Sophie Jump is a theatre designer, and the granddaughter of George Devine and Sophie Harris, and great niece of Percy Harris. She designs for both theatre and dance and is Associate Director and co-founder of the dance company seven sisters group, renowned for their site-specific work, and a Director of the Society of British Theatre Designers. In 2006 she curated « When Marcel Met Motley », an exhibition at Chelsea Space, London. This was about the collaboration between Motley and Marcel Breuer, who designed the interior of the London Theatre Studio. She is currently writing a book about the London Theatre Studio and Old Vic School.

You can visit her website by clicking here : http://www.sophiejump.co.uk/

From June 1931 to 1934 the Compagnie des Quinze visited London yearly, performing their productions at the Arts Theatre Club, for three or four week seasons. The public, and the theatre community in particular, received them with rapture, and John Gielgud and theatre producer Bronson Albery invited Saint-Denis to direct an English version of the Quinze’s ‘Noé’ by Andre Obey.

Although Saint-Denis wanted to use his original designer, Madeleine Gautier, the mother of his youngest son Blaise, for the costumes he was persuaded to meet Gielgud’s designers, the design firm known as Motley. Motley consisted of three women named Elizabeth Montgomery and sisters Margaret, known as ‘Percy’, and Sophie Harris. The Motleys set about persuading him that they could design the whole show. Percy and Elizabeth remembered that having seen the Compagnie des Quinze they had decided that they; ‘would like to work with that man’. Percy remembered the meeting well:

We said, “No. If we do the sets, we want to do it all.” We had a tremendous battle. And then Liz did sketches of the set, and Michel looked at them and said, “That I know I shall have.” And Liz said, “Not unless we do the costumes.” How we had the audacity, I don’t know, because we were very, very anxious to work with him.’

Clearly their audacity did not put off Saint-Denis, and indeed may have encouraged him to feel he had found people to work with who would respond well to his own creative ideas. He recalled later that he had felt immediately at home: « I had found my milieu, in this atmosphere where technique, invention, and freedom blended. »

The Motley’s business manager, close friend, and later to be husband of Sophie, was a young actor named George Devine. Devine and Saint-Denis seem to have got on well right from the start. In his book The Theatre’s of George Devine Irving Wardle suggests that this was partly due to Devine’s fluent French but also that:

‘Their agreement over the kind of theatre they wanted was probably the strongest bond between them. But, to begin with, the best clue to their sympathy is that they made each other laugh.’

The production of ‘Noé’, though a success, did not receive the acclaim of the Quinze version and this was partly due to the difference in acting style which Saint-Denis found it hard to adjust to. He had been used to working with an ensemble and the English actors were very much entrenched in the star system. For example Saint-Denis asked that the actors attend rehearsals in bathing suits, a request that caused so much consternation that it was agreed that only the younger actors would comply. The older actors were allowed to rehearse, as usual, in suits and hats or high heels and dresses.

He was persuaded by the experience that the only way to create the kind of actors needed for such a production would be to train them. The Compagnie des Quinze were facing financial difficulties and although Saint-Denis tried to secure funding for them from his supporters in England this proved impossible and he came to the conclusion that the best route forwards would be to disband the Quinze and open a drama school in London.

The London Theatre Studio opened in 1935 with Saint-Denis as Managing Director, Devine as the Assistant Director and Manager, and Motley running a design course (it was the first drama school to incorporate design into its curriculum). There was also a course for theatre technicians and for directors (then called producers). The name Studio was deliberately chosen and the intention was that a company would be formed and fed by students, designers, directors and technicians from the Studio, but also that professional actors would be able to take classes to refresh or extend their skills.

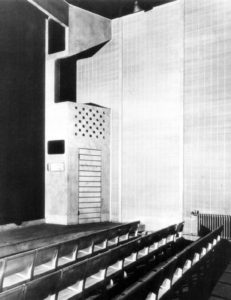

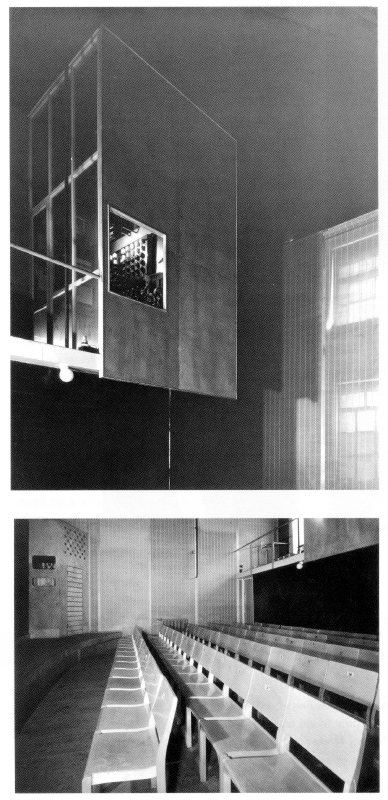

Opening first in Diaghalev’s old practice rooms in Beak Street the students rotated classes to share the limited space. The LTS was supported by many big names in the theatre world including John Gielgud, Tyrone Guthrie and Laurence Olivier, many of whom contributed financially to the Studio. Finally, with a generous financial help of a production student named Laura Dyas, they were able to purchase an old factory in Islington and bring in the architect Marcel Breuer to convert it into premises for the Studio.

Although the LTS only survived for three years, being prematurely cut off by the outbreak of war in 1939, its spirit was carried on under a new name and form in the Old Vic Theatre School (1947-1952) and the influence of both schools is still felt. Saint-Denis was influential in bringing to mainstream British theatre improvisation, mask work and an emphasis on physical and vocal agility. The schools highlighted the importance of the text and a knowledge of the style of the period in which the text was written. It took theatre seriously. In his book A Positively Final Appearance Alec Guinness, who had attended classes for working actors at the LTS, writes that;

‘I somehow knew in my heart that a door had been opened for me. It dawned on me that acting could have an affinity with the arts.’

The students of the LTS and Old Vic School carried the style, techniques and attitudes they were taught out into the professional world, some becoming teachers themselves. In this way the influence of the schools is so profound that we hardly remember a time when there was another way of working.

Sophie Jump